How to Split Wood Easily: A Complete Step-by-Step Guide

Splitting wood is a valuable skill that can enhance your self-sufficiency and provide a reliable and renewable source of fuel for various purposes (especially if you live near/in the woods as we do) and it also looks sexy as hell. Unless you’re wearing an ill-fitting sweatshirt whilst chopping, as I am in the videos below…

Regardless, chopping and storing firewood is a skill that’s both essential and oddly satisfying — turning trees into warmth — and this guide will walk you through the process, tools, and techniques necessary for effective wood splitting and firewood storage over time.

Tools You Need for Splitting Wood

Essential Gear

Safety Gear

Optional Tools

Understanding the Basics of Wood Splitting

Probably obvious, but just in case: wood splitting is a vital task on any homestead that offers numerous benefits. If you live around trees and one inevitably falls down, maybe across your driveway or some other undesirable spot where you can’t just leave it be for nature to run its course, you’ll need to first use a chainsaw to buck it up into manageable tree rounds.

Then, at some point, you can slice these tree rounds into smaller pieces of wood, which will be a sustainable energy source for heating and cooking — either indoors in a fireplace or wood burning stove, or outdoors in a fire pit or Solo Stove kinda thing.

The act of splitting also encourages physical exercise and outdoor activity. It’s a skill that warms you twice, as they say — once when you chop it, and again when you burn it.

But if you’ve never done it before, it’s also one of those processes that simultaneously looks impressively difficult and way too easy. Setting yourself up for success starts with understanding the wood itself — what to split and when to split it.

Real quick, here’s a favorite tongue twister: “I split a sheet, a sheet I split, upon the splitting sheet I sit.”

Types of Wood Suitable for Splitting

Hardwoods vs. Softwoods

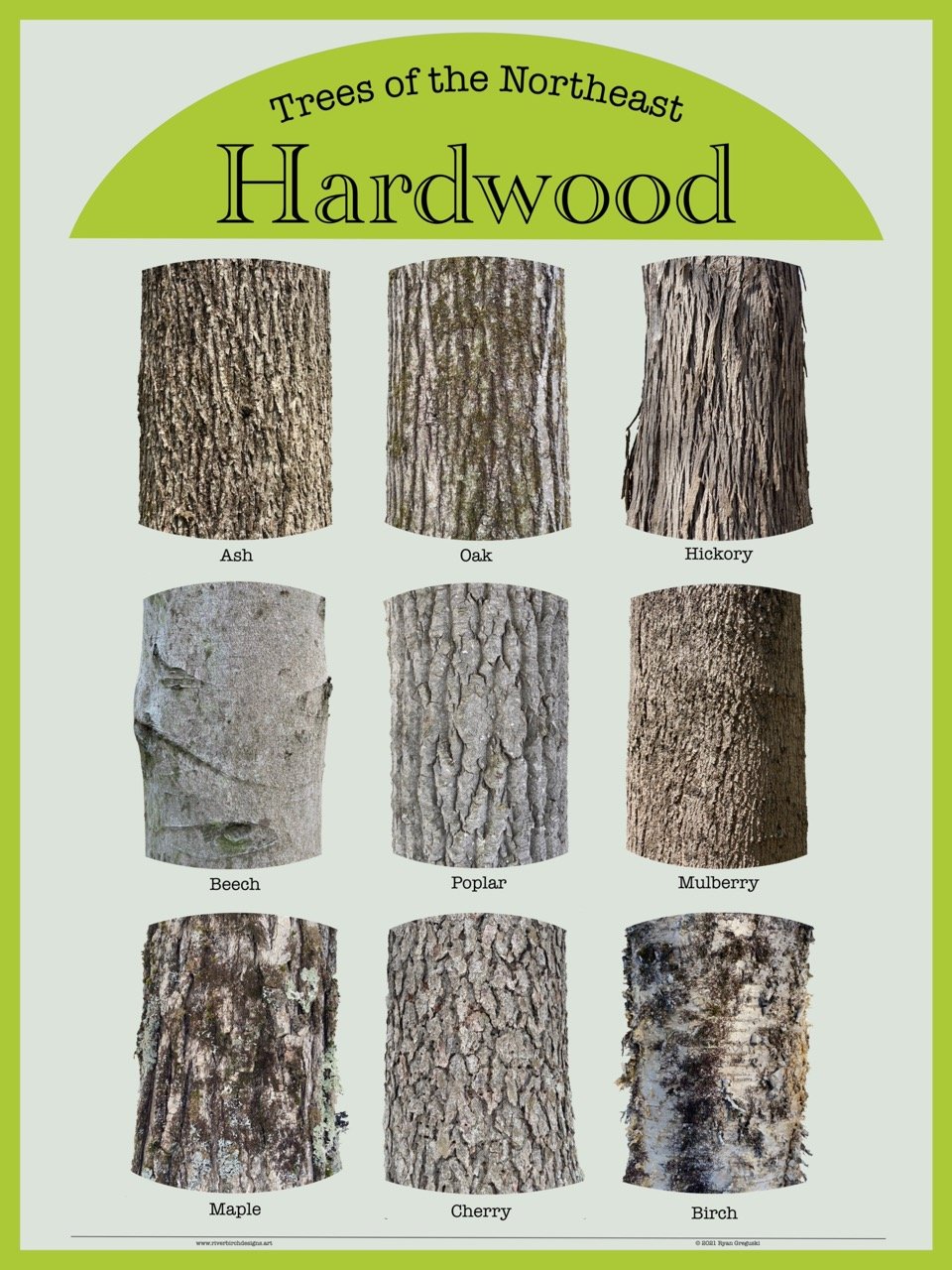

Knowing the type of wood you’re working with will help you choose the right technique and tools for efficient chopping. Tree identification apps like PlantNet, My Tree ID, and PictureThis are great (especially worth the money if you’re also use it year-round to identify garden vegetation, invasive species, weeds, poison ivy, etc.) and can help you ID a tree by its leaf, flowers, or bark.

Hardwoods

Includes oak, hickory, maple, ash, beech, birch, cherry, elm, and poplar, pretty much in that order of preference. Like, oak is the top-shelf stuff that burns longer and stronger, while poplar burns more quickly with less heat output.

These typically take a little longer to season, like 1-2 years (see below), but they burn well indoors, and some offer a little aesthetic or aromatic bonus.

They’re denser and, therefore, require more force to split, so a heavy maul or splitting axe is recommended.

Softwoods

Includes pine, spruce, fir and cedar, and generally stuff with more resin or sap mixed in, which means they make good kindling and can help get a fire going, but they also produce more undesirable creosote which can eventually clog up a chimney and generally be a bummer.

These season faster, like 6-12 months, and are better to burn outdoors where you don’t have to worry about sticky buildup.

They’re less dense and easier to split with a lighter tool.

Mixing and matching can be an effective strategy – a smorgasbord of wood types gives you different properties from the fast-start stuff to get the fire going combined with slow burning dense material to keep it going overnight, if that’s your thing.

Green vs. Seasoned Wood

“Green” wood is not actually green, it’s usually a brighter white. Green means it’s freshly cut and still contains high moisture levels, making it tough to split and burn.

“Seasoned” wood has had time to dry out — anywhere from 6 months to two years — making it much easier to split due to reduced moisture content. It might be a bit darker, already has some small splits or “checks” in it (and also may have some insects and other critters who’ve taken up residence in there). Ultimately, if you want to make a fire, you want seasoned, dry wood.

To optimize your wood-splitting efforts, you want to work with seasoned wood whenever possible, which means planning ahead. You can’t just fell a tree and expect to cut it up and throw it in the fireplace a few days or weeks later.

Wood Grain Considerations

Trees grow vertically, which is why it’s easier to split wood lengthwise rather than across it. Picture a string cheese: using your fingers, it’s much smoother to peel off strips lengthwise rather than sideways, right?

So cutting wood along the grain is ideal, looking for any natural splits, openings, or “checks” in the wood, especially the “rays” (the lines that run from the center of the wood to the bark). Knots (where branches once stuck out of the tree trunk) and other irregular grain will complicate matters when splitting, often requiring wedges to pry that sucker apart.

Timing, and When to Use a Hydraulic Log Splitter

According to the experts at STIHL, the ideal time to cut firewood is in late winter or early spring, which gives your wood maximum drying time before the next burning season. But let's be real – if you're reading this in the dead of winter with a cold house, any time is a good time to start chopping.

If you need to split a lot of green wood quickly — like if a big tree just came down and you’ve chainsawed it into large tree rounds but want to break it down further into manageable pieces of firewood to stack and season — I highly recommend biting the bullet and renting a hydraulic log splitter for a weekend. I did this when we first moved in, and don’t get me wrong it still wasn’t “easy.”

Maneuvering large tree rounds into position is tiring work, but it can expedite the process of turning a fresh tree trunk into firewood.

There’s a hydraulic log-splitter behind this pile that deserves a good amount of credit.

Step-by-Step Guide to Splitting Wood

Okay, so now that you’ve got some seasoned logs, let’s get into technique. Chopping wood may look cool, but it isn't about channeling your inner lumberjack and hacking away like a madman. It's more art than science, a dance between you and this powerful, once-living thing.

In my pre-apocalyptic novel, We Can Save Us All, power outages are common and when the characters’ generator runs out, they discuss differing wood-splitting styles:

Owen especially liked dude stuff. The How To tasks that show up in men’s magazines. He loved chopping wood, but when it came to technique he was a novice, just hacking away at cold logs.

“You are the Brute Squad,” David said.

Mathias was more methodical. It’s like deconstructing the tree, he said, piecing it apart it in the opposite way it grows. He’d start along the perimeter, slicing off the bark. Then, you look for natural cracks that can be exploited as starting points. Drive in a few wedges. Lop off the outer layers. Once it’s exposed, you take its heart, the center-most ring. Everything after that is super easy.

“All of this is probably a metaphor for something,” he said.

Prepare the Wood and Work Area

Let's face it: axes are sharp, and trees are heavy. Before you start splitting, here are tips to keep all your digits intact:

Wear Proper Gear: Steel-toed boots, gloves, and safety glasses are your new best friends. Keep in mind the worse case scenarios: sweaty hands could send an axe flying; a glancing blow could send the axehead flying in the wrong direction and hit your foot, even with a good chop, splinters or pieces of wood could fly into eyes. Respect the potential danger here and don’t take this shit for granted.

Check your tools: Ensure your maul or axe head is secure and sharp. A dull axe is more dangerous than a sharp one. An unsecured axe head could fly off the shaft and hurt someone.

Select a safe location and platform: You want an extremely stable chopping block here, like a wide and level tree stump or a very heavy tree round. The platform should be solid enough that the force of the axe will split it, but soft enough that when the axe slices through it can embed in the platform without damaging the tool (i.e., a wet, decaying tree stump may be too soft; a slab of concrete is too hard and will damage the axe head or cause it to ricochet). The platform should be about 12” elevated from ground level — you want the axe to meet the top of the log squarely when you strike downward.

Clear your area: Make sure you have a stable footing and no obstacles around you – no kids or pets wandering around, no branches, tools, or objects to trip over, nothing above your head that’s going to snag during your swing, etc.

Stabilize the log: When you place the log on the chopping block, it should rest squarely, centered on the platform. If the log was cut at an angle, it won’t rest properly on the platform so you’ll want to use a chainsaw to square it off first. Make sure it contains no nails or metal pieces, and ideally few knots. And it should be dry wood, not wet wood.

Avoid injury and fatigue: If you have back or shoulder problems (really any injury) or are exhausted, don’t try to chop wood. It’s a tiring, full-body endeavor, and most injuries occur when fatigue has set in and you’re making poor decisions. Take frequent breaks, don’t overdo it, there’s always tomorrow.

The Splitting Technique

Starting Position and Aiming:

Face the log squarely, with your dominant side just slightly forward, not a sideways “boxer’s stance.” Imagine the axe missing the log: you’d want the axe head to end up between your feet rather than going straight into your toe. Stand with feet pointed straight and shoulder-width apart for stability. Keep your knees slightly bent for flexibility.

Begin with the axe or maul head resting on the top of the log, seated squarely on the chopping block. Especially when you’re starting out, it might take a minute to get comfortable with the length of your axe and the overall striking distance. This is the “aiming” phase–aim for the center of the log. Not your shins.

The top of the log (where the axe will strike) should be flat and level, not angled (which could cause a glancing blow).

Place your dominant hand near the head of the axe or maul. Your other hand should be at the base of the handle. Hold firmly but not too tightly – allow for some movement. Your grip will naturally tighten as you swing.

The Backswing:

Lift the tool overhead, extending your arms high.

As you lift, allow your dominant hand to slide down the handle, meeting your other hand.

Straighten your back and knees, rising slightly on your toes for maximum height and leverage.

The Downswing:

Begin the downward motion by dropping your arms and bending slightly at the waist.

Let gravity do most of the work – a maul is intentionally heavy, so guide the tool rather than forcing it.

The Strike:

Aim for the center of the log or any visible cracks or checks.

Just before impact, straighten your arms and snap your wrists for extra power.

Follow through with the swing, aiming to embed the axe head in the chopping block. Don't try to stop it abruptly.

Complete the Motion:

Allow the tool to continue through the log (if it splits) or into the chopping block.

Bend your knees to absorb the impact and protect your back.

Reset for the Next Swing:

If the log didn't split, carefully work the axe or maul free.

If it's stuck, try turning the log over and striking the butt of the axe-head onto the chopping block, which may split the log or jar the axe loose.

Assess and Adjust:

Take a moment to evaluate your last swing.

Adjust your aim or technique as needed for the next attempt.

Troubleshooting Common Challenges

Glancing Blows

Focus on accuracy over power. A well-placed hit is more effective than a strong, off-center one that could carrom off into something undesirable.

Don’t try to split angled wood or anything too thin. Give yourself something to aim at.

Check your aim and adjust your stance if needed. If you’re consistently missing, it may be that your chopping block is too high or low.

Stuck Tool

Don't try to wrench it free. Instead, use the log's weight to your advantage by flipping it over and then smashing the butt end of the splitting tool against the chopping block.

If necessary, use a second tool (like a wedge, driven in by a baby sledgehammer) to help free a deeply stuck axe or maul.

Twisted or Knotty Wood

Look for natural weak points or cracks to target.

Consider using a splitting wedge (or two) for particularly troublesome logs. If you’re consistently having issues splitting, the wood may be too knotty/twisty to split well, or it may still be too green.

Storing Firewood: The Key to Dry, Efficient Burns

Okay, so chopping is only half the battle. Maybe three quarters. Knowing how to properly store wood ensures your hard work doesn't go to waste.

The Golden Rules of Firewood Storage

Elevate: Keep your wood off the ground. This prevents moisture absorption and deters pests. Use pallets, build a simple rack with pressure-treated, ground contact lumber, or buy a metal log rack.

Stack Smart: Create a stable pile that allows air to circulate, typically with bark side up to shed water. Think of it as a game of Jenga, but one where you want it to stay standing. If you want to get fancy with it, there are some unique stacking methods you can try:

Row-stacking: the standard, traditional, parallel method

Cross-stacking: alternating layers, perpendicular to each other

Holz Hausen, Norwegian, and Amish methods: various circular stacking methods

Cover Up: Use a tarp or purpose-built cover to protect your wood from rain and snow. But don't seal it completely – you want some airflow to prevent mold.

Location, Location, Location: You may want multiple locations, actually. Consider storing your seasoning wood away from your house to discourage unwelcome critters from making your home theirs. And then you may want a smaller log rack close to the house for seasoned wood ready to be burned, close enough that you won't curse the distance on cold nights.

First In, First Out: Use the oldest wood first. It's like rotating stock in a store, but instead of expired milk, you're avoiding rotten wood. You’ll likely lose some wood at the bottom of your pile to mold, fungus, and general rot. It’s cool. Ashes to ashes.

Conclusion

Mastering the art of wood splitting not only provides practical benefits but also fosters a deeper connection with nature. By following this guide, you can ensure efficient and safe wood splitting practices.

Now that you’ve got a good pile of firewood, consider investing in a nice wood burning stove to help heat your home!